Building Post-Disaster Resilience

This post was originally published by David Lallemant on ResilientUrbanism.org in July 2013. The original post can be found here.

I have been working on an assessment of Haiti’s housing recovery and reconstruction process. Specifically I have been tasked to look at how “disaster risk management” was or was not integrated into reconstruction in order to build disaster resilience. I have found this project really interesting, and so I plan to share it, but in digestible pieces surrounding particular ideas.

“Building back better” has been all the rage in the post-disaster reconstruction community. The concept is not particularly novel, but re-branding it with alliteration has made all the difference (it also makes great acronyms like BBB and B3!). The basic idea is that we should not rebuild vulnerability. Unfortunately, the term has pretty much stayed at this level of abstraction: catchy but not particularly descriptive. What does “Building Back Better” mean? Victoria asked similar questions in her post on “what do we mean by recovery?” Specifically she asked “if recovery is a process then what is the intended outcome?” What I am looking at is not outcome as reconstruction in a physical sense (number of buildings reconstructed, etc), but outcome in terms of resilience.

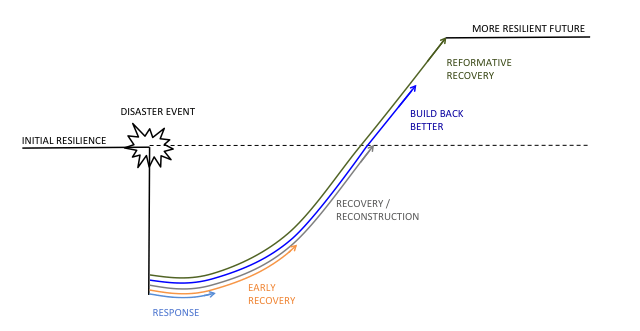

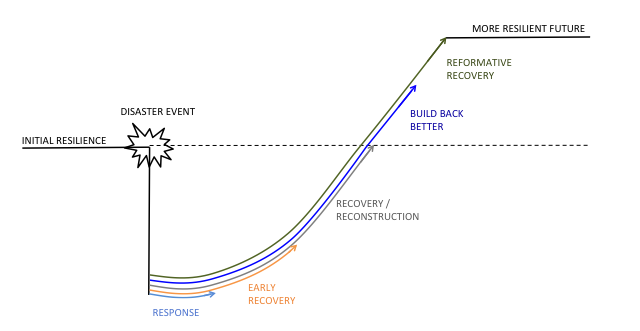

While I was thinking about all this, I started drawing a diagram of how “resilience” progresses through disaster recovery (in an ideal case). This simplified diagram attempts to conceptualize recovery as a process to build resilience, as well as highlights new terminology in the field: “reformative recovery.”

Recovery as a process of resilience building. In this framework, disaster risk reduction in reconstruction means having a steeper trajectory (shorter time) and a higher end-point (more resilience). Diagram by David Lallemant

The humanitarian/reconstruction sector often discusses post-disaster work in terms of “phases,” usually broken down into “response,” “early recovery” and “reconstruction.” This terminology of “phases” is problematic since it implies that these are strictly chronological. In a way, this artificial decomposition of the reconstruction timing has been a self-fulfilling prophecy, since agencies have designed their processes and programs according to this concept (for instance “humanitarian” agencies can often only fund activities linked to so-called “response” and “early recovery”). Hence I will call these “processes” rather than phases, and emphasize through parallel lines that all these activities actually start right after the disaster (or should).

This brings me to the key messages I am attempting to communicate through this diagram:

(1) The response, recovery, reconstruction (and other) processes start at the same time. The attention and funding for each process changes in time, but fundamentally they need to start right after the disaster, at least at the planning level.

(2) The importance of distinguishing these processes is that each is linked to specific activities and goals in terms of resilience:

- Response: the process is one of stabilization, preventing further death or injuries due to the immediate crisis.

- Early Recovery: the goal here is to address the extreme vulnerability following the disaster, such as lack of access to safe shelter, lack of physical security, basic economic security etc.

- Recovery/reconstruction: strictly speaking, recovery and reconstruction means going back to the previous state. Hence this is a restorative process to the original level of resilience.

- Building back better: As mentioned previously, what is rebuilt should be more resilient. Since “building” has a material reality, the term has mostly referred to increasing the resilience of the built environment. It is a classic (and very important!) engineering approach, focused on construction guidelines, material quality etc.

- Reformative recovery: The concept of “reformative recovery” is set in contrast to the traditional “restorative recovery.” The aim of reconstruction has usually been to restore to the previous state. Any improvements from this previous state is usually focused solely on the physical infrastructure (build back better). Reformative recovery by comparison is a process through which new dynamics for disaster resilience are created, often through government and social reform. It is a “new normal” as Victoria mentioned in her post. I stumbled upon the term “Reformative recovery” in this article. I have not seen the term used anywhere else, but I really love it!

(3) Finally, these processes create path-interdependencies (hence the parallel lines). In other words the earlier processes (not so much earlier as those with most funds at the early stages) set the initial direction, therefore creating path dependencies for other activities. This can be very problematic in the absence of common targets. In Haiti following the 2010 earthquake for instance, many of the “temporary” solutions significantly constrained the path for safe permanent reconstruction.

Ultimately this model does not fundamentally change the current framework of thought on reconstruction and disaster resilience, but I hope to give it a bit of a nudge and/or provoke some thinking about the way post-disaster reconstruction can reform the dynamics of risk.

One Response

[…] This week the earth has definitely reminded us of its often violent temperament. A 6.9Mw earthquake struck rural Myanmar on Wednesday, a 7.0Mw earthquake struck Southern Japan on Friday, and a 7.8Mw earthquake struck Ecuador on Saturday (note this earthquake was as powerful as the 1906 earthquake!). These have already caused nearly 400 fatalities and the numbers are still rising. The communities that have been destroyed will take years to fully recover. Hopefully through recovery they will build more resilient communities. […]