Guest blog: Stories from the field in Nepal

Written by Jasna Budhathoki, Kathmandu Living Labs.

Informatics for Equitable Recovery (IER) is a research collaboration to improve post-disaster information systems and decision support tools. In this project, we aim to address certain limitations in the information provided in post-disaster impact assessments, which are typically centered on physical damage. To do this, we measured the recovery of communities and households affected by the Nepal 2015 earthquake to identify the physical, social, economic, and geographic obstacles to recovery four years after the earthquake.

In May 2019, the IER team recruited 12 field researchers to collect household-level data to study the impacts and reconstruction progress of the Nepal earthquake that occurred four years before. The researchers underwent a two-day training at Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL) before they went to the field. During the training, they learned about the basics of field research: what is a researcher’s role in the field? How do they develop rapport with respondents? What are potential ethical issues? Over the two days, the researchers closely worked around these questions and learned about the best practices of field research in post-disaster contexts, including how to handle sensitive questions and ensure that respondents gave informed consent to be interviewed. After completing the training, the field researchers left Kathmandu to conduct surveys in earthquake-hit districts that had been randomly selected by the IER team. The districts included Dolakha, Makwanpur, Nuwakot, Okhaldhunga, Ramechhap, Rasuwa and Sindhuli.

The researchers participate in field research training by Dr. Nama, Executive Director, Kathmandu Living Labs.

Researchers take mock interviews as preparation for field interview.

Our research team from KLL (including my colleagues and I) went to Okhaldhunga, an earthquake-hit district 200 kilometers away from the capital city of Kathmandu. We learned that Manebhanjyang municipality in Okhaldhunga district was facing severe drought for 14 years. Due to the drought, the farmers — constituting the majority of the population in the village — could not produce crops and therefore had lost their major source of income. Many of them had to take loans to even feed their family members one decent meal a day.

Through our field surveys and interviews, we learnt that the earthquake in 2015 had aggravated their situation. Following the earthquake, drinking water taps had dried up in our survey area. Now, the villagers get water through pipes from a river 7 km away from the village. The taps flow only one time during the day and the duration of water flow is always uncertain. We also saw women carrying river water in plastic bottles, placing them in doko (bamboo basket) and carrying it uphill for hours it took to trek home. What we observed in the field reveals how the effects of the earthquake was not limited to housing damage–in the case of Okhaldhunga, it was scarcity of water. This means, for some affected areas, returning to a sense of normalcy requires not only the reconstruction of buildings but also the restoration of the water supply system.

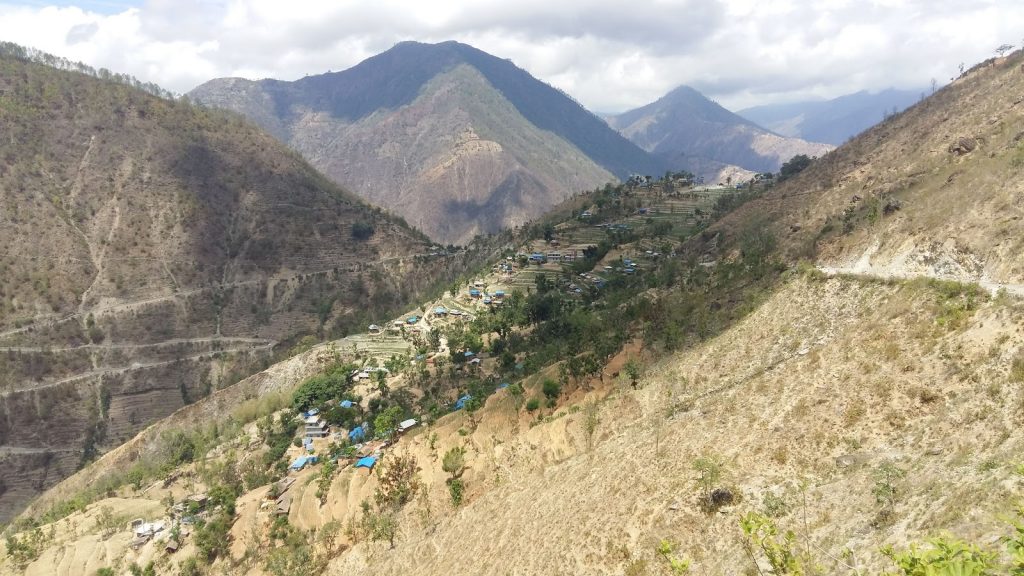

Manebhanjyang, Okhaldhunga waits for rain

A woman carries water in a doko (bamboo basket)

One of the households I surveyed in a community in Okhaldhunga described the challenges her family had to confront when first given the cash grant for reconstruction. Facing many other constraints, including their pre-existing debt, the difficulties of the drought, and pressures on their livelihoods, they decided not to use the cash grant. They have not spent the money on anything fearing that the government will ask them to return the money back since they haven’t started the reconstruction yet.

Our field surveyors encountered many similar stories highlighting the complexity of recovery in a context where other hazards and livelihood risks also constrain household decisions to reconstruct. Our forthcoming analysis of the survey data will go into more detail on trends across different factors determining recovery and need.

When we initially reached the field, we were surprised that many of our respondents were elderly. Later, we found that their children were away for work (Kathmandu, or foreign countries especially in the Middle East). Since the older residents relied on their children’s income and didn’t have incomes of their own, they preferred to keep the houses unreconstructed. Although some might claim that remittances from children working abroad should help households be in a better position to reconstruct, our field experiences suggested something slightly different. Despite having children sending remittances back home, some households still did not have enough capital to cover the expenses of reconstruction. Additionally, since most houses in Okhaldhunga had damage grade level lower than 3 (minor cracks without collapse), and the repairs were minimal, the locals used stones and mud from their own backyards to cover the cracks.

We also encountered some households that had faced challenges with reconstruction despite receiving some technical assistance. One household we spoke to had to stop reconstruction midway because they were told that their reconstructed house no longer met safety criteria even though they had received assistance at an earlier stage. Over the next few months, our team will be analyzing the field data more systematically to confirm some of these anecdotal observations.

Despite living in poverty and hardship, the locals welcomed us into their homes. They offered us local homemade mohi (mixture of skimmed milk and water) even when they themselves faced food scarcity. Some of the respondents were so glad to share their stories of struggle because, as they said repeatedly, there is hardly anyone who they can share their stories with. Although most members agreed that they lived in a close-knit community where villagers helped another in times of need, the older people who had less contact with other members of the village and whose houses were isolated from the rest showed great interest in talking to us and helping us capture their stories in depth.

Going to the field, meeting people, and listening to the stories of recovery from the earthquake has helped us understand the value of each interview we collected during our time on the field. Each response has now been transferred to a huge spreadsheet consisting of hundreds of rows and columns. For a field researcher, each row is much more than numbers and words. Each row records certain information about a family desperately struggling to recover from the effects of the deadly earthquake. Despite their struggle with their limited capital and resources, we could see that almost every family in the village was affluent in simplicity, kindness, gratitude and their sense of belonging in the community. Though we were on field seeking for data, we found something much greater than what we were looking for – the originality in the ruralness.

Okhaldhunga surveyors from Kathmandu Living Labs(KLL)