Five years later: equitable recovery research in Nepal

Exactly 5 years ago — on April 25th, 2015 — an Mw 7.8 earthquake struck Nepal, causing an estimated 9,000 fatalities and displacing over 3.5 million people. Disaster remembrances like these are always challenging events to work through — they are a time to assess and report on the work done in the recovery process, yes, but they also push us to recognize and reflect upon the very real human costs that continue to be borne by survivors across Nepal. This fifth-year memorial is particularly difficult because it comes during the Covid-19 crisis, which threatens the livelihoods of many and has pushed Nepal, like much of the world, to lock down to slow the spread of the virus.

Our research on Nepal’s recovery — the Informatics for Equitable Recovery project — sought to understand these disaster impacts and recovery processes holistically. With the completion of our final report and the 5th year memorial, we want to share some core findings of our work from over the last two years.

3 key messages from our research

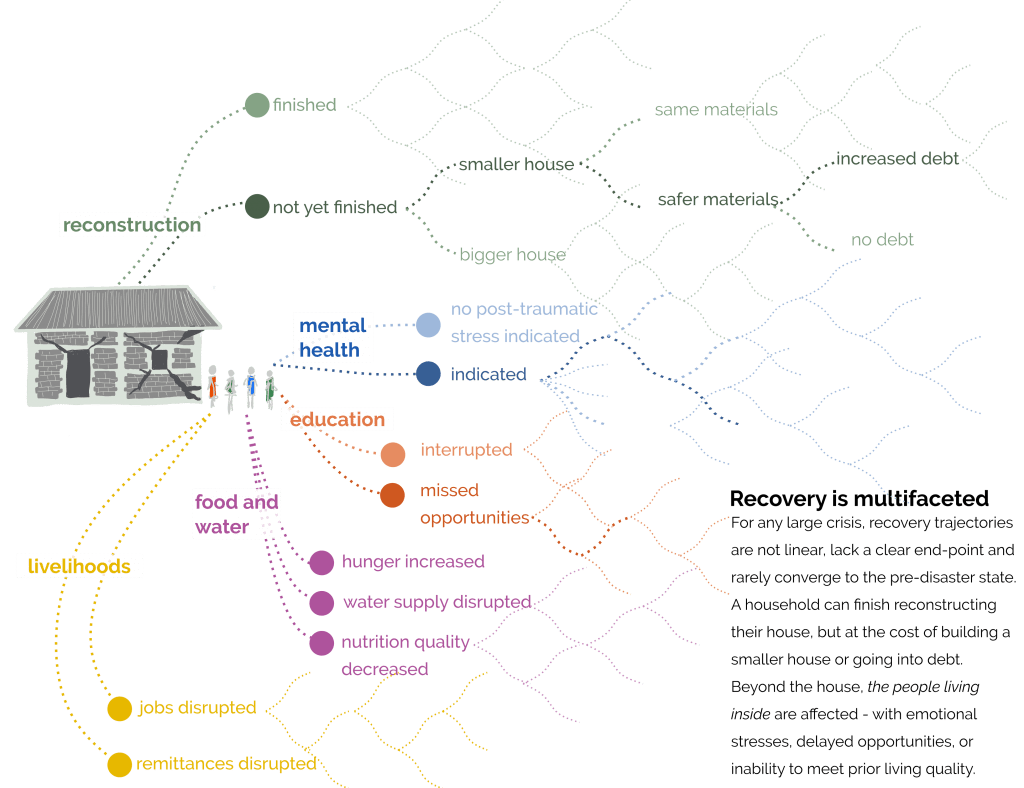

Recovery is not a straightforward, or linear, process; there are many different trajectories of recovery, with varying tradeoffs involved.

- Many households we interviewed are indeed ‘building back better’ in the sense that many rebuilt houses are incrementally safer in an earthquake compared to the pre-earthquake house. The National Reconstruction Authority of Nepal sent many thousands of field engineers to reach millions of residents across very remote terrain; this technical assistance was instrumental in leading to improved earthquake safety in the rebuilt homes. Yet in many cases, residents have had to take on substantial debt and sell off important assets in order to cover their costs of reconstruction.

- While the push to improve building stock and disburse tranches of aid after engineering assessments has been helpful for improving safety, more attention can be paid to other aspects of household wellbeing — like providing support for mental health, lower-interest loans, and livelihoods.

- Our interviews with community leaders across affected districts in Nepal also highlighted the need for focusing on communal services and infrastructure that were disrupted by the earthquake, especially roads and water supply systems.

It is possible and valuable to improve the accuracy of post-disaster evidence, like building damage maps, by rapidly integrating multiple data sources.

- After any earthquake, a sense-making process begins: agencies scramble to collect data to understand where and how people are affected. In Nepal, the National Reconstruction Authority deployed field surveyors to assess damage and provide technical assistance across multiple districts, supported by volunteers.

- So far, most damage integration tends to be done in an ad-hoc way: stakeholders are presented with many different maps, uncertainties, and possibilities of the damage and must select or combine them however they see fit.

- Part of our research aimed to facilitate the process of rapidly assessing needs after a disaster. To achieve this, we developed a methodology that can integrate limited field-based observations with modelled and remote-sensing based proxies of damage into a single damage map. For more details on this methodology, see our final report.

Households will have different needs after a disaster; it’s important that post-disaster evidence reflect those differences thoughtfully.

- Beyond the immediate humanitarian response to a major disaster, the focus of many involved – residents, community leaders, national governments, and experts – is often on rebuilding or repairing the houses, community buildings, and infrastructure that was damaged or destroyed. Yet as all these groups know all too well, physical reconstruction is not the only need.

- It is possible to define a ‘post-disaster persistent need’ metric that helps predict the locations of households facing challenging paths to recovery, using vulnerability and recovery data acquired from past disasters.

- Developing such a metric for affected regions of Nepal — based on data we collected and publicly available proxies — suggests ways to link recovery data with risk reduction efforts, especially by identifying intractable obstacles to recovery.

- Information systems and post-disaster evidence should be sensitive to issues of equity, access, and differential need to equip stakeholders with evidence that helps identify and address systemic, persistent vulnerabilities.

Reflecting on ‘informatics for equitable recovery’ amidst Covid-19

Our research consortium first convened in 2018 to develop new ways to approach post-disaster information. We wanted to do research that produced usable tools and outputs, and which reflected the experiences of earthquake-affected households faithfully. In the two years since we began doing this work, our collaborations with civic organisations and researchers in Nepal have shaped the way we understand disaster damage, recovery, and need. We hope to make all of our tools and findings openly accessible, and most of our work can already be found on our project website.

We have no expertise in epidemiology. Yet as fellow humans, we reflect upon how our intersecting vulnerabilities — from Covid-19, natural hazards, and more — call for intersecting, multidisciplinary partnerships that recognise the systemic roots of vulnerabilities and how these are distributed unevenly across our communities. Covid-19 is making clear what our research on disasters has also shown: in crises, there is often no moment of ‘returning to normal’, whether to an idealised pre-disaster state or the same pre-event vulnerabilities. Our communities are transformed by crises, and it is up to us collectively to see that that transformation reduces, rather than multiplying, our vulnerabilities and that recovery plans support those with the most need.

Acknowledgements: This project, Supporting Equitable Disaster Recovery Through Mapping (Nepal), submitted in response to the 2017 call for proposals by the World Bank’s Development Data Group (DECDG) and the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (GPSDD), is supported by the World Bank’s Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building (TFSCB) with financing from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID), the Government of Korea, and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland. The project is also supported by the Earth Observatory of Singapore and National Research Foundation.